The result of the 2024 parliamentary election in the constituency of West Dorset marked a radical departure from the unbroken line of Conservative candidates elected to Parliament from 1868 onwards. It is therefore an opportune moment to review the history of the parliamentary representation of the County over the past 200 years.

This first of two posts examines the history of electoral representation prior to The Great Reform Act of 1832 and how that reform, together with the numerous further measures of reform which followed it, altered the electoral representation of the County.

- A) THE CONSTITUENCIES.

Prior to the 1832 Great Reform Act the County of Dorset elected two members, and the Boroughs of Dorchester, Lyme Regis, Bridport, Corfe Castle, Wareham, Poole and Shaftsbury also returned two members each. Weymouth returned four members, two being representatives of Melcombe Regis, which originally had been a separate borough.

The Great Reform Act of 1832 abolished the Corfe Castle constituency, reduced Lyme Regis’ representation to one M.P. and that of Weymouth to two members but increased the number of the County’s members from two to three.

Subsequently, the 1867 Representation of the People Act (also known as the Second Reform Act) reduced the representation of the Borough of Dorchester and of the other Boroughs in the County to one M.P. each.

Finally, the number and boundaries of Dorset constituencies were radically reformed by the Redistribution of Seats Act of 1885 which aimed to equalise the population comprised within each constituency in England. To this end, it split Dorset County into four divisions, North, East, South and West each represented by one member. In addition, the constituency of Dorchester and the other Dorset borough constituencies were abolished.

- B) THE FRANCHISE.

To qualify to vote in the County elections prior to 1884 it was necessary to be a “forty shillings freeholder” of land, or to have that amount of income derived from a Dorset estate or properties generating that amount of income per annum. The qualification for Borough elections was different and varied from place to place, but usually consisted of residence, property qualification, tenancy status and/or possession of the status of a “freeman” or membership of the Town Corporation.

The Representation of the People Act of 1884 (known as the Third Reform Act) extended the franchise to all men owning property valued at £10 or over or paying an annual rent of that amount in all English towns and counties. The Representation of the People Act of 1918 further extended the franchise to all men over the age of twenty one, regardless of the former property qualifications, and also to women over the age of thirty who owned property in the constituency in which they lived with a rateable value exceeding £5, or whose husbands owned such property. Finally, the Representation of the People ‘Equal Franchise) Act of 1928 extended the franchise to all women over the age of twenty-one.

- C) THE CONDUCT OF PRE-REFORM ELECTIONS.

Nominations were often agreed beforehand by the two main parties, the Whigs and Tories, and in such cases the agreed candidates were returned unopposed without a poll. Polling was generally spread over several days and electors often travelled great distances to attend and vote at one single polling booth.

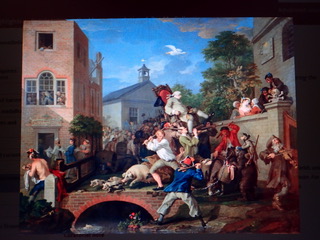

Voting was public. Each elector was required to appear personally at the polling booth, usually in public on a platform, in order to justify that he was qualified to participate in the vote and then to name his choice aloud in front of the surrounding throng (Photo 1 shows a print by William Hogarth of election hustings).  Consequently, voters were often accompanied by their retinue of supporters to protect them from intimidation. Prior to voting, the electors, together with the wider public, could listen to speeches delivered by the candidates and their prominent supporters from the hustings; they were also often entertained by bands and treated liberally with food and drink. Onlookers often were also treated to drink even if they were not qualified to vote!

Consequently, voters were often accompanied by their retinue of supporters to protect them from intimidation. Prior to voting, the electors, together with the wider public, could listen to speeches delivered by the candidates and their prominent supporters from the hustings; they were also often entertained by bands and treated liberally with food and drink. Onlookers often were also treated to drink even if they were not qualified to vote!

Elections were regarded as a great event in the same way as the major seasonal fairs, and attracted crowds from the town and the surrounding countryside who came to witness the spectacle and who were often drunk and disorderly! The series of four paintings, and of the corresponding prints, created by William Hogarth in the 1750s record how the process worked, with very little exaggeration (see Photo 2 of pre-election feasting).

- D) THE 1831 DORSET COUNTY ELECTION.

The bitterly fought election of 1831 is a perfect example of a pre-reform election, and it was certainly Hogarthian in nature!

A general election had previously been fought throughout the country in May of that year, almost exclusively over the proposed Reform Bill. The Bill had been presented to the House of Commons by the new Whig Prime Minster, Earl Charles Grey, and had been blocked by the opposition Tories, thus provoking a dissolution of Parliament and a General Election.

In Dorset three candidates had stood for the two County seats: Edward Portman of Bryanston, a pro-reform Whig, Henry Bankes of Kingston Lacey, an anti-reform Tory, and John Calcraft, a minister under the former Tory Prime Minister Lord Wellington but who had since then embraced the cause of reform. Portman and Calcraft had been elected.

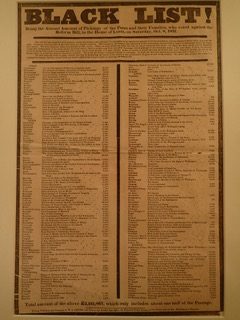

Feelings were running high in the country. The election had been fought with a great deal of bitterness and resulted in the Whig government under Lord Grey being returned with a landslide majority of 136 seats. There were many satirical prints, songs, handbills and posters printed and distributed (see Photo 3 of a pro-reform poster listing the salaries and the value of other perquisites received from the Crown by anti-reformer members of the House of Lords).

On 11th September Calcraft committed suicide by cutting his throat with a knife in his London home, in all probability because of depression induced due to the ‘cold shouldering’ by his former Tory colleagues in the House since his re-election. A by-election was therefore promptly called to replace the deceased M.P. and the Whigs quickly nominated Lord William Ponsonby of Canford Manor, close to Wimborne, who was obliged to resign from his parliamentary seat in Poole in order to stand.

The Tory candidate, Lord Anthony Henry Ashly Cooper of Wimborne St Giles, the eldest son of the 6th Earl of Shaftesbury, was announced just in time on 27th September. Initially he was reluctant to stand, fearing he would incur ruinous costs during the campaign. Under pressure from fellow Conservative grandees, he finally agreed to do so and was obliged to resign his position as the M.P. for the Borough of Dorchester (subsequently his younger brother Henry was elected unopposed to his former seat in another by-election held in October of that year).

Polling in the County by-election was to take place in Dorchester, the County Town, and the campaign commenced on 29th September. Ashley took up residence in the Kings Arms for the duration of the campaign. The opening election hustings were held on Poundbury Fort, which was then just outside the boundaries of the town. Speeches were given by the proposers and seconders of both candidates, and then by the two candidates themselves, before a crowd estimated to have been between five and six thousand strong, Ashley had difficulty in making himself heard despite being a talented orator because of the sustained heckling from Ponsonby’s supporters. At the close of the speeches Henry Damer, the Chairman of the meeting, called for a show of hands and declared it to be in favour of Ponsonby. This was rejected by two members of Ashley’s election committee who requested the holding of a poll of all qualified electors. This was accepted.

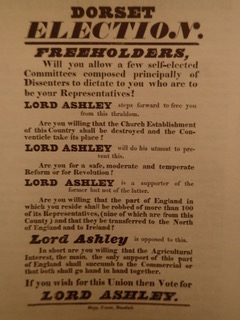

This opened a campaign of 15 days of canvassing, speech making and voting until the close of poll which was fixed as Monday 17th October. The campaign was marked by violence on the part of Ponsonby’s supporters and the distribution of defamatory tracts and songs principally by Ashley supporters. Photo 4 shows a poster indirectly libelling Ponsonby.

Ashley argued that the proposed reform was dangerously radical and risked setting off a train of ideas which might lead to revolution. The French Resolution, which had commenced only 40 years previously and led to the execution of that country’s monarchs, resulted in some twenty years of bloody European conflict and to a threat of French invasion. This remained fresh in the memories of the older half of the population and Photo 4 illustrates the anti-reform rhetoric promoted during the campaign. Ashley argued that the tide in favour of reform, which had led to the landslide in favour of the Whigs in the General Election earlier that year, had changed and that Dorset could consolidate that shift in opinion. He declared himself in favour of a much more moderate reform which would not abolish as many existing Borough seats in favour of the new industrial towns. The attention of the nation, and of its press, was therefore focussed on the campaign and this helps to explain the passions displayed during the fortnight of campaigning.

Each evening the tally of that day’s voting, together with the cumulative totals of votes to date, were announced to a throng gathered round the hustings on Poundbury Hill Fort where the electors of the day had announced their preferences publicly. At the end of the fifth day Ashley’s initial lead was reduced to one. The following day Ponsonby was ahead, but with the same miniscule majority. From the ninth day Ashley drew ahead again. Then, on the evening of 8th October, the House of Lords rejected the Reform Bill by a majority of four votes. This inevitably increased the ire felt by Ponsonby supporters.

Individual acts of violence, mainly against Asley supporters, were reported from the evening of the tenth day. These included assaults committed by a member of the legal profession, who was acting as an electoral agent, by his fellow professional acting for the adversary! The Times newspaper reported on the eleventh day that, “very few elections have taken place where so much acrimonious feeling has been manifested as by the agents and partisans of the two candidates”.

On Monday 17th October a large crowd started to gather for the last day of polling. Ashley had ended the poll on the Saturday evening with an overall majority of twenty-seven. As was customary, no further polling had taken place on the Sunday. The Dorset County Chronicle, published in Dorchester, estimated that by midday on that Monday the crowd had swollen to several thousands and, “As the poll proceeded steadily, though slowly, in favour of Lord Asley, the irritated feelings of the lower order of the Reformers could no longer be restrained, and a large body of them, armed with sticks, rushed to the vallum which crowns the hill, and dislodged the band of Lord Ashley from the position that it had there occupied; the supporters of his Lordship were compelled in self-defence to resist, and a general conflict ensued between the two parties.” It was also stated that some of the booths which had been erected on the site for the occasion were dismantled to provide supplementary weapons for the adversaries. Calm was only restored when a troop of 200 Yeomanry rode up to the Camp from the town barracks armed with sticks and dressed in civilian clothes.

Polling closed at 3.00pm and Lord Ashley was declared the victor half an hour later by a margin of just 39 votes, having received 1,847 votes as against 1,811 for Ponsonby. Ashley received 65 votes from Dorchester and Fordington voters as compared to only 17 who voted in favour of Ponsonby. According to the diary of Mary Frampton the victor was then escorted back to the King’s Head by 300 to 400 mounted supporters, amongst them many members of the Yeomanry (see Photo 5 of a painting by Hogarth illustrating a similar ‘Chairing of the Member’).

The Yeomanry were called to intervene once more when Ponsonby’s supporters attacked the booth and the carriage of Henry Damer, the High Sheriff, and of Phillip Williams who had acted as the Assessor for the contest. The Assessor’s role in the conduct of a poll was vital since he was required to verify the identity and voting qualification of every person who presented himself to vote and to adjudicate disputes whenever his intervention was requested by a candidate. Those qualified to vote were not listed in a register and the property qualification could only be established by referring to the relevant Rates Book.

According to the census of 1831 the population of the County comprised 159,385 men, women and children. It has been estimated that only just above 4,000 men were qualified to vote i.e. 2.3% of the total population. As noted above, 3,658 of them voted, an extremely impressive turnout of 9I.4.%, demonstrating that the national contest over parliamentary reform captured the imagination of the population.

Both parties had made allegations of imposters having been presented to vote. For example The Times reported that the Tories alleged that, “coach loads of individuals who had no shadow of a franchise were brought to the poll to tender for Mr. P.” and that the Whigs had countered that the Assessor had allowed paupers to vote, and that, “many of these men are upwards of 80 years of age , some blind, others imbecile and numbers unable to walk”. Allegations were also made that some voters had received bribes in return for their votes.

After the result had been declared there remained a total of 434 contested votes to investigate and adjudicate, more than enough to alter the result of the election. Matters were not helped by the fact that Phillip Williams, a Barrister in London, was a member of the prominent Dorset landowning Williams family who were known to be Tories. As a consequence, Ponsonby decided to petition the House of Commons to invalidate the election. The petition was rejected by the House on 19th March 1832.

Both candidates were nearly ruined by the debts that they incurred during the campaign; Ashley’s expenses exceeded £15,000 and may have been as high as £28,000. They included hundreds of pounds spent on drink and food for the electors and their followers, together with transport costs for electors living far away from Dorchester, including for London residents. He had built up impressive slates at The Anchor, The Chequers, The Green Dragon, The Mariners, The New Crown, The Old Crown, The Phoenix, The Plume of Feathers, The Queen’s Arms, The Red Lion, The Ship, The Wood and Stone, and of course The King’s Arms. Bills were also incurred in hostelries through the County, including Weymouth, Portland, Maiden Newton, Winfrith, Corfe Castle, Milborne St Andrew and Gillingham. Ponsonby’s expenses are reputed to have totalled £30,000 and he was left out of pocket for years.

Following the election result rioting took place in Blandford on the evenings of 17th and 18th October, as well as in Poole and Wareham. In Sherborne a mob broke all the windows of the Digby family’s castle before being dispersed by a troop of Yeomanry. In Dorchester the supporters of both sides celebrated or mourned the result in the town’s many hostelries during the course of the evening and serious clashes occurred in Fordington when some of Ashley’s supporters tried to return to their homes in the countryside, culminating in a confrontation on Greys’ Bridge between fifty to a hundred Ponsonby supports who had emerged from the pubs where they were drinking and a group of twenty to thirty farmers on horseback. Lord Asley himself was obliged to take a circuitous route to return to his home in Shaftesbury and felt obliged to travel with a pair of loaded pistols in his carriage.

It was feared that disturbances would erupt again on 5th November, Bonfire Night, and on that evening the guard at Dorchester Gaol was reinforced and special constables were sworn in to keep the peace in the town. However, the evening passed peacefully, and the pro-reformers limited themselves to burning effigies of Lord Ashley on the bonfires throughout Dorset.

During the course of these troubles the Phillips family reinforced the security of their house in Dorchester, which was already equipped with stout window shutters reinforced by iron bars, by replacing the original fanlight over the front door with an ingenious new fanlight incorporating a mirror which enables the inhabitants to view who is at the front door and on the pavement and road in front of the house (see Photo 6, taken from inside the entrance hall).

Following the rejection of the Reform Bill by the House of Lords during the by-election, the Whig Premier Lord Grey was obliged to request King William IV to prorogue Parliament, since the rules did not allow for a defeated bill to be reintroduced in the same session. In 1832, during the new session, Lord Grey reintroduced a slightly modified Reform Bill and in March it was passed with an increased majority in the House of Commons. The Tories in the House of Lords then blocked progress on the Bill by voting several wrecking amendments. When it became clear to the Premier that King would not agree to create enough new Whig peers to enable the measure to pass, he tendered his resignation to the King who reappointed Lord Wellington as Prime Minister.

After a great deal of further political agitation and demonstrations in favour of reform, particularly in May 1832, Lord Wellington proved incapable of forging a coalition in favour of more moderate reform, obliging the King to recall Lord Grey. The latter then finally managed to steer the Bill through the House of Lords after the King undertook to create as many new Whig peers as necessary to achieve support in that house, leading the Tory peers to abstain when the measure came before them again. The Great Reform Act thus received Royal Assent on 7th June 1832.

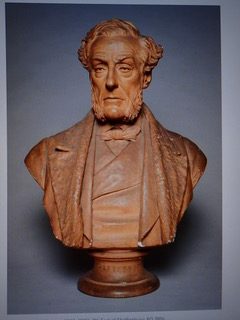

Lord Ponsonby, together with Lord Ashley, were returned as members for the County in a further General Election held in December 1832. Subsequently Lord Ponsonby retired from Parliament in 1837 and received a peerage. Lord Ashley also retired from the House of Commons on inheriting the title of 7th Earl of Shaftesbury from his father in 1851. From 1833 onwards he became the Country’s leading social reformer and philanthropist, introducing several Factory Acts and measures to reform employment in the mines, restricting employment of women and children (including outlawing child chimney sweeps), improving education and housing, and reforming the law on lunacy. Photo 7 shows the bust of the Earl as a senior Victorian statesman in Dorset County Museum.

IAN GOSLING,

CHAIR OF DORCHESTER CIVIC SOCIETY

Recent Comments