I recently visited the former Royal Hospital for Seamen in Greenwich, part of which is now occupied by the Maritime Museum, and I was struck by its close links to Dorset.

THE EARLY GREENWICH PALACE

Its site on the south bank of the Thames, downstream from the City of London, has been occupied by royal palaces since 1447 when it was acquired by the wife of Henry VI. Until the building of Whitehall Palace in the 1530s it was one of the principal palaces of Henry VII and Henry VIII, serving as the first (and last) port of call for visiting foreign ambassadors and dignitaries.

When Whitehall Palace was completed, it replaced Greenwich as the seat of government and the latter became a royal country retreat much favoured by King Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth I and Anne of Denmark, the wife of her successor James I.

THE STUARTS AND INIGO JONES

Anne commissioned Inigo Jones to build a hunting lodge in the new classical style to the north of the old palace, now known as the Queens House. However, the building was not finished by the time of her death in 1619. Queen Henrietta Maria, the wife of Charles I, James’ son, revived the project, and it was completed in 1638 (see Photo 1).

After the Civil War and the restoration of Charles II in 1660, the dilapidated red brick palace was gradually demolished to make way for a new palace to the design of John Webb, the pupil of Inigo Jones, which was designed to rival the splendour of Louis XIV’s Versailles. However, by the time of the death of the architect in 1672 only the shell of one of the three planned ranges of buildings had been completed. The precarious state of the King’s finances made the project unaffordable, and the King decided to concentrate instead on updating Windsor Castle.

One of the principal causes of the King’s change of heart was the high cost of Portland stone which had been used for the Queen’s House and which was chosen to give grandeur and longevity to the proposed new palace. Thus, the first link to Dorset nearly killed the project!

Together with the Queen’s House, the shell of the ‘King’s House’ dominated the river, marooned on a building site when Charles’ brother James II inherited the throne. In 1687 James, who had commanded the Royal Fleet in many battles at sea, conceived of the idea to continue the construction project but to modify so that it served as a hospital for the care of seamen injured in the service of their country or facing difficulties finding accommodation on their retirement.

WILLIAM AND MARY AND CHRISTOPHER WREN

In 1691 Queen Mary, whose husband William III had ousted James II (her father) in 1688, decided that she would implement his project. Her decision was triggered by the huge casualties sustained during the bloody five-day, and successful, naval battle against the fleet of Louis XIV off La Hogue.

Sir Christopher Wren, the King’s Surveyor who had designed extensions to Chelsea Hospital which housed injured and retired soldiers, offered to design and supervise the completion of the project without charge. He had by then designed the new St Paul’s Cathedral and since 1675 was engaged in its construction, which would only be completed at the end of 1711. He was of course very familiar with the qualities of Portland Stone which he had chosen to use for the structure of the Cathedral.

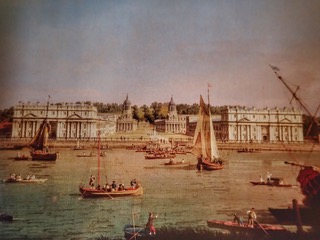

In modifying John Webb’s original design for the palace, he was inspired by Les Invalides, the impressive hospital inaugurated in 1678 in Paris, commissioned by Louis XIV from Jules Hardouin-Mansart to house injured and retired soldiers. The Greenwich Hospital was designed to be magnificent in order to reflect and magnify Britain’s naval power, situated as it was at the maritime entrance to London through which all foreign visitors to London were obliged to pass, and also to invoke patriotic feelings and encourage enlistment into the Royal Navy (see Photo 2).

After the death of Queen Mary from smallpox in 1694, her widowed husband William confirmed Wren’s commission and the latter chose Nicholas Hawksmoor as his Clerk of Works.

In 1698 Wren was instructed to add a domed Hall into the design to serve as a dining room for ceremonial occasions. On 11th October 1700 Wren wrote to Thomas Gilbert, Overseer of the King’s Quarries on the Isle of Portland: “This is to authorize you to raise out of His Maj’s quarries….Two Thousand tuns of Portland Stone…for the service of the Royal Hospital at Greenwich, and you are hereby required to transmit to me a true account from time to time, the quantity you send the time when, and the Vessell on which you load, and for soe doeing this shall be your Sufficient Warrant”. The reverse side of the order is annotated that it took a year to fulfil the order. Wren visited the quarry on Portland on several occasions to check the quality of the stone being provided for the project.

QUEEN ANNE

William died in 1702 and he was succeeded by Queen Anne, sister of his late wife Mary. By 1703 the structure of the Hall had been completed (see Photo 3) and the decision was taken to decorate the interior with a minimum of sculptured features and to decorate the walls and ceiling, once plastered, with ‘trompe l’oeil’ paintings of historical and allegorical scenes. Wren suggested that James Thornhill, the leading British exponent of such work should be commissioned to execute the work and he was appointed in 1707.

JAMES THORNHILL

James Thornhill was born in Melcombe Regis in 1675, the son of an impoverished Dorset squire and at the age of fourteen he was apprenticed for seven years to the London painter Thomas Highmore, who specialised in decorative painting. He was also influenced by the Italian and French artists, Antonio Verrio and Louis Laguerre, who had been employed by Charles II and members of his court to create grand scale mural paintings. In 1707 he was just completing an important commission from the Duke of Devonshire to decorate the saloon, staircase and a suite of rooms in Chatsworth, and it is likely that the Duke was responsible for him being appointed at Greenwich.

The design work for the project, the priming of the plaster surface and the painting of architectural details and the scenes themselves, covering over 42,500 square feet, took nineteen years in all and covers the Entrance Vestibule, the Lower Hall and the Upper Hall.

The numerous gods, goddesses, allegorical figures, sovereigns and famous historical figures, together with the sterns of two Men of War, which decorate the Baroque ceiling of the Lower Hall surround King William III and Queen Mary, representing Peace and Liberty, trampling underfoot a representation of Louis XIV. The representation of winter (old man with white beard) on the northern margin of the scene is in fact a portrait of John Worley, the oldest naval pensioner then living in the Hospital, who died at the grand old age of 96, despite regular bouts of drunkenness! (see Photo 4).

The centre of the ceiling of the Upper Hall features a double portrait of Queen Anne and of her husband Prince George of Denmark (see Photo 5). On its west wall, visible even from the Entrance Vestibule, and framed by a triumphal arch, features George I, the third monarch to have witnessed the execution of the work, together with his descendants. On the lower right-hand side of this, perhaps the most stunning and life-like of the murals, James Thornhill himself is shown, his hand extended to his last Royal Patron, perhaps pleading for outstanding fees! (see Photo 6).

On its west wall, visible even from the Entrance Vestibule, and framed by a triumphal arch, features George I, the third monarch to have witnessed the execution of the work, together with his descendants. On the lower right-hand side of this, perhaps the most stunning and life-like of the murals, James Thornhill himself is shown, his hand extended to his last Royal Patron, perhaps pleading for outstanding fees! (see Photo 6).

The murals are now as bright as they were when just completed following detailed restoration work costing over £8.5 million, and lasting from 2016 to 2019.

In 1718 Thornhill was appointed History Painter to the King and, two years late, Sergent-Painter and a knight, whilst he was painting the interior of the dome of St Pauls Cathedral. In 1725 he acquired Thornhill House near Stalbridge, North Dorset, which his family had lost in 1686, and transformed it into a Palladian country house (see Photo 7). In August of 1726, he added his final touches to the Greenwich Painted Hall. Meanwhile he had been elected as M.P. for Weymouth and Melcombe Regis in 1722 (he was then returned at the subsequent election of 1727) and had painted a large canvass of the Last Supper for St Mary’s church in the town, which is still in place (see Photo 8).

In August of 1726, he added his final touches to the Greenwich Painted Hall. Meanwhile he had been elected as M.P. for Weymouth and Melcombe Regis in 1722 (he was then returned at the subsequent election of 1727) and had painted a large canvass of the Last Supper for St Mary’s church in the town, which is still in place (see Photo 8).

His other works visible in Dorset are the mural he created to decorate the staircase of Sherborne House (Photo 9)  and a painting of the Resurrection (Photo 10)

and a painting of the Resurrection (Photo 10) is displayed in Dorset County Museum. Two coach panels painted by him for King George I’s state coach are in the Museum’s store (Photo 11).

is displayed in Dorset County Museum. Two coach panels painted by him for King George I’s state coach are in the Museum’s store (Photo 11).

He died in Thornhill House in 1734, aged 59, and his succession was assured by his son-in-law William Hogarth, whose portrait of a very old man is also displayed in the County Museum.

These two substantial connections between Greenwich Hospital and Dorset also exist in relation to St Pauls Cathedral, which was built at the same time, of Portland Stone, by Sir Christopher Wren and whose dome is also decorated by James Thornhill. Both monuments signal the importance of Dorset to Georgian architecture and decorative art at the beginning of the 18th Century.

Recent Comments